The evolution of the science of ampelography

It’s all too easy to believe that once a scientific advance has entered into common usage it must be the best and only way to solve a problem. However, just as how in the world of medicine a good surgeon will examine a patient thoroughly, in addition to looking at the results of an MRI scan, it turns out that this also applies to ampelography – the study and identification of grape varieties.

Dr Anna Schneider © Michel Grisard

At a talk given by Dr Anna Schneider, an Italian specialist in the study of grape varieties, who works in Piemonte for the Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection, part of the National Research Council of Italy, she explained the differences between traditional ampelography and modern ampelography, with the latter using DNA profiling techniques. She went on to argue why it is important that both techniques are used together.

Pierre Galet still likes to have his say. © Michel Grisard

The talk was part of an annual event in February staged by the CAAPG (The Pierre Galet Alpine Centre of Ampelography), based in Savoie, which attracts audiences from across France, Switzerland and northern Italy, principally from the Alpine arc. Pierre Galet himself – widely known as the ‘grandfather of ampelographers’ or the most important ampelographer of the 20th century, who had just turned 95 – was present and in fine form, posing eloquent questions to several of the speakers.

Classical versus modern

What Schneider called ‘classical ampelography’, as practiced by Galet, originally identified varieties by using the attributes of the vine – its leaves, shoots and grapes. In addition, identification techniques are used in the laboratory, such as examining primary substances like proteins and enzymes in the grapes and measuring the anthocyanins, tannins, terpenes and so on that appear in the wine. Modern ampelography or ‘molecular ampelography’, as Schneider called it, is a small branch of genetics that not only identifies grape varieties, but can also be used to study the relationships between them.

This is known in English as DNA profiling and is conducted by analysing the genetic markers of a vine and comparing them with those of other vines. If all genetic markers are identical, the varieties are identical genotypes (a genotype is the genetic make-up of an organism, in this case the vine). If there is at least one different marker, the vines will be of two different genotypes. Several identical genetic markers indicates a probable family relationship between the vines.

The advantage of DNA profiling over traditional methods is that it can be done at any time of the year by examining tissue matter from any part of the vine sent to a laboratory from any vineyard in the world. It can even be applied to young vines. Due to the fact that it is automated, Schneider claimed that the process was a relatively inexpensive way to achieve highly detailed results. These results provide a genetic fingerprint for each vine type. On the other hand, classical ampelography requires no sophisticated equipment, can utilise human experience and hypothesis along with using historic photographs, paintings and drawings for comparisons. These results can later be verified using the DNA techniques.

Why identification needs to be right

The correct identification of grapevines is necessary in particular for the legal reason of correct labelling for nurseries (and the subsequent wines), as well as for the traceability of wines. It’s also needed to check on the origins of rare, rediscovered historical grape varieties and to further the cause of ‘archeo-ampelography’.

Yet, in vine collections at nurseries around the world there are said to be 5-10% errors in the identification of scions (the vines themselves) and up to 20% errors in rootstocks. Famous errors cited by Schneider were that Italian Refosco was believed to be identical to Savoie’s Mondeuse, until DNA testing in 2009 proved otherwise. Also, Müller-Thurgau was for almost a century considered to be a Silvaner x Riesling cross due to mislabelling, but has since been identified as a Riesling x Madeleine Royale cross. Another famous mistake revealed more recently (not cited by Schneider) was the discovery in Australia of what were thought to be Albariño vines which in fact turned out to be Savagnin, due most likely to mislabelling in a Spanish nursery.

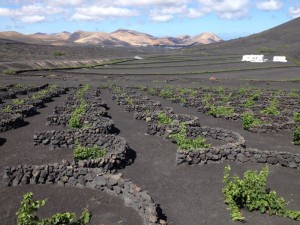

It’s hard to unravel the story of how Malvasia arrived in Lanzarote © Wink Lorch

Schneider believes that using DNA profiling alone is not fool proof. Mix-ups also happen through the sheer disbelief that the same vine can crop up somewhere so far away. For example, the same variety can exist under different names on both sides of the Alps. She also illustrated this with the journey of the Malvoisie variety, which had historically travelled from somewhere east of Greece to Lipari, and was then included in cargo on the classic sea voyages that ended up in Madeira and the Canary Islands. The story of Zinfandel’s origins is another well-known one that took years to unravel, all because different names were used everywhere. It took knowledge on the ground, along with DNA analysis, to come up with the final conclusion that Zinfandel was not only identical to Primitivo in Italy and to Crijenak Kaštelanski in Croatia, but that historically in Croatia it was named Tribidrag.

Ampelography’s importance for the future

Schneider emphasised that studying the genetic relationship between grape varieties is important for two main reasons: the first is that by verifying the pedigree and origin of each variety and understanding how and where it evolved historically, the wine can be marketed more successfully; the second is that by studying the genetic heritage of the whole population of grapevines and the relationships between them, one can establish so-called ‘core collections’ of vines.

Training on the ground for people working in laboratories on DNA profiling is essential, Schneider maintains, otherwise mistakes are inevitable. In this way traditional ampelography retains its importance.

Schneider concluded by saying that the genetic heritage of grape varieties is crucial and she also gave a glimpse of the future. She explained that using DNA testing for traceability in the actual wines themselves is difficult today since wines contain very little of a grapevine’s DNA and the DNA in wine is often degraded. However, techniques are advancing at great speed and a breakthrough is close to solving this by using new methods of genetic sequencing.

Note: Dr Anna Schneider’s talk was delivered in French. I used the introduction to Robinson, Harding and Vouillamoz’ Wine Grapes to verify certain terminology.

This article was first published in Circle Update, the newsletter for the Circle of Wine Writers, for which I am editor. The article was copy edited by Robert Smyth. My thanks to him and to Michel Grisard, retired Savoie vigneron and relentless supporter of rare grapes, for the photographs.